Collaboration Sankey and Macleod 2024

PETRICHOR / smelling the rain by Katherine Sankey and Anna Macleod Curated by Helena Tobin

“Everything dreams. The play of form, of being, is the dreaming of substance. Rocks have their dreams, and the earth changes.” - Ursula K Le Guin, The Lathe of Heaven

It starts imperceptibly, with a leak in a roof, trickling in unnoticed until it makes itself known in a sprawling web of cracks amidst mildew and mould.

Or it advances over a beach, inch by inch, shrinking the littoral zone, that interstitial space between land and sea, until it laps at boardwalks, invades cities, erodes the cliffside foundations of houses, causing what’s human-made to slide away, off the known edge of the world.

Or a once-in-a-century storm arrives: a river swells, breaks its customary if malleable boundaries, rushes outward, flooding villages, sweeping away houses and cars and people. It is an increasingly common occurrence, in an age when unprecedented weather is more norm than outlier.

Always its logic is inexorable, its memory long, immediate, and assured; all water remembers that it once covered the earth. Water is the substance of change; it never stays the same. Water teaches us that the solidity of things and places is illusory. Given the climate emergency, we should perhaps aspire to the state of water; if we did, we’d be better prepared for the future.

In this exhibition curated by Helena Tobin, Katherine Sankey and Anna Macleod consider our relationship to the fluidity of water. Macleod makes drawings based on studies of the hydrological cycle, while Sankey delves into the adaptability of forms. Both work intuitively with their materials— a thread unravelled from a ball (Macleod), plumbing tubes and found tree limbs (Sankey)—to transform the gallery space in a collaboration that explores change in the Anthropocene.

Chthonic is an apt word for Katherine Sankey’s oeuvre. Tree limbs and plumbing tubes are interwoven and connected to create serpentine sculptures that undulate along the gallery floor with a life of their own, welling up from sinks and attaching themselves to other fixtures, as if underworld creatures have opened a portal in the gallery. A porcelain washbasin is nearly overturned by a dense tangle of branches linked by copper and brass seal rings; one limb pierces a wall. Heavy ceramic objects colonise a gallery floor with bone- or coral-like mineral structures. A dried bush hangs from the ceiling, talons protruding from the bottom. And what looks like a computer mouse emerges from a tangle of vines, still attached to its hiding place by umbilical wires. It is a quare yet familiar world that Sankey has built, which seems to rise from an unconscious both monstrous and human.

Finding an affinity between human and nature, Sankey uses industrial yet homely materials like plumbing and electrical tubes as visual analogies to the root, as in the roots of a tree or the hyphae of a mycelium network. The plumbing tube is imagined as a prosthetic limb, willfully extending itself through space. By animating this kinship, Sankey suggests how humans mimic nature: like roots, plumbing extracts and supplies water, expelling its byproducts as waste. The boundary between the human and the other—nature conceptualised as separate from the human—is porous, open to interpenetration.

Neither purely natural nor purely human, these hybrid objects are wholly uncanny, all the more for the commonplace materials usually associated with the domestic and industrial realms, ostensibly domains under human control. Pipes carry “clean”, commodified nature (water, electricity, gas) into the bourgeois home and pump “bad”, metabolised nature outside. They are part and parcel of functional systems which, despite human dependence on these systems, are consigned to marginalised zones. The home may host the elements of these systems, but it also attempts to conceal them from plain sight, as if there is something abject about them. Only when pipes break down, do we notice their existence; only when nature seeps into the foundations of our built world, do we realise how easily they are undermined. By fusing pipes with vegetal elements (outside/the other, also often concealed or dominated), Sankey’s constructions point to the porosity not only of the domestic, but also of matter itself, in its ability to be recombined in new and startling ways.

The sight of plumbing pipes summons images of sewage, the flow of literally malodorous waste, abject matter which we prefer kept unseen. By exposing the process of waste management in the clean white space of the gallery, Sankey alerts us to human ambivalence towards the processes by which our byproducts—usually considered outside of ourselves—are handled and expelled.

Penetrating walls and attaching themselves wherever they wish, the works have an unsettling relationship with architecture. They reveal the potential of architecture: not to assure human control and domination over space, but to show how flimsily it contains our activities and desires. Sankey’s sculptures seem to exert their own will, with the intent to invade, penetrate, and expand into our world. Like mycelium networks, they self-reproduce and colonise. They creep and crawl and exude new limbs with which to take the best advantage of their environments. Engaging with the gallery space, they improvise at will, plugging themselves wherever, almost offhandedly, to feed opportunistically on their environment. They are potentially parasitic, disquietingly, because that suggests the parasitic nature of modern human life—our technologies intervene wherever there are resources to exploit and plunder, allowing capital to extend itself.

In colonising the gallery space, Sankey’s hybrid objects infer an alternative and unhomely reality, emerging from the refuse of our world. In that parallel world’s strange and deviant shapes, we might glimpse the future of a materialist and technological ecosystem that is proving unsustainable. Sometimes I think an apocalypse doesn’t announce itself with a big bang, in swift, cataclysmic events that occur simultaneously. Instead, it arrives incrementally, in a series of minor catastrophes, slowly spreading through the understory of our lives until it has crept over and devoured what we thought stable and enduring. Given time, humans might adapt. But in an anthropocenic future, a resilience appropriate for extremely volatile circumstances will be required, demanding new ways of being; what is human might well become unrecognisable.

Water’s movement from the ocean to the atmosphere and back to the Earth is known as the hydrologic cycle, a host of ceaseless phenomena influencing all life on the planet. In 2022, Anna Macleod developed the Hydrologic Water Cycle Series of Wall Drawings at CCI in Paris. This ongoing project visualises the logic of water in a series of drawings in which Harris tweed thread is fixed in the gallery space with tape, in a continuous line that winds along the walls. Unravelled from a single ball of thread, the line ripples, undulates, twists, meanders, tumbles, crests, breaks, and eddies, sometimes leaping from the surface, crisscrossing the space as if to defy containment. The line is intuitively determined by Macleod’s experience, memory, and knowledge of the hydrological cycle, inscribing patterns of precipitation, condensation, run-off, and other hydrological processes. Rivulets, streams, surges, sprays, cascades, ducts, and deluges: all manner of aqueous phenomena are evoked.

Here drawing is not meant to faithfully represent the visible. Instead it summons the visible using the body as medium, engaging performatively, even ritualistically, with the gallery environment. To see the drawing post-performance is to imagine a body in the gallery space, instinctively activating theories of hydrological processes. Viewers are reminded that a body is part of a being that feels and senses the world, and in turn produces marks to register even invisible phenomena, of which she is a participant just by being. In drawing, then, thinking assumes form.

Macleod’s drawings are landscape drawing in the negative. In traditional landscape representation, the lay of the land is depicted, for the pleasure and profit of its intended viewers. Here, the line’s restive movement only suggests the seen environment’s topography, its seemingly stable and fixed features. Rather, flows are rendered as tangible lines; what is made apparent are the invisible forces of water and air, as mist, cloud, and other meteorological phenomena are fixed into image. By inverting the conventions of landscape representation, Macleod questions the Western colonial imaginary of the world as terra nullius, in which encountered landscapes are conceived as blank spaces ideal for the inscription of Empire’s economic activities.

By assuming all space as empty yet potentially productive (i.e. profitable), the doctrine of terra nullius overlooks water’s agency, its will; it fails to recognise droughts, or rising sea levels, presupposing that everything, including water, is to be controlled and dominated, through methods of containment and concealment. But in the negative image of landscape, Macleod has rendered visible the potential, not of Empire or of the Anthropocene, but of nature. “Water symbolises the whole of potentiality,” wrote Mircea Eliade, “it is fons et origio, the source of all possible existence. Water is always germinative.” Water has no shape of its own, but can take any shape, move from liquid to solid and back again; it has infinite possibility. The drawings allude to the potential of regeneration that water yields in myth. Multifarious, water is ever in a state of flux, on the verge of change and movement.

If water is a germinative substance, one might discern a consciousness behind its activities and processes. Water moves through the world as if it has a will, an intent to migrate into every quarter, however small or large. In pagan Europe, water’s sentience was a given; deities inhabited holy wells, rivers, lakes, and ponds. If water is capable of thought, its movement, then, is a form of thinking, just as drawing is a medium for and a form of thinking.

The drawings train the eye to see the world in terms of the flow of water, at a macro- level. In their graph-like appearance, they connote the model of a system, linking microcosm (the gallery) to macrocosm (the world). Used since prehistoric times, diagrams are symbolic representations of information using visualisation techniques. Examples include portolano charts, star maps, and mandalas. Diagrams attempt to make sense of the world’s complexity through a combination of the pictorial and abstract. Meaning is extracted by correlating parts of the diagram, conjuring new and unexpected relationships. The mandala is a cosmic diagram, which draws on meditation and trance to visualise the nature of cosmic reality, allowing its user to attain spiritual transformation. Similarly, while based on theories of hydrological processes and drawing on the conventions of the scientific image, Macleod’s intuitively produced drawings are spiritually attuned to the workings of water, that is, to its will, drawing the viewer into a meditative relationship with its processes.

Does water dream? Consider petrichor. When rain falls, it stirs and releases geosmin, a molecule harboured by the soil bacteria Streptomyces, which mixes with ozone in the air and volatile oils secreted by plants, thus producing petrichor. Described by James Joyce as “a faint incense rising upward through the mould from many hearts,” petrichor is a pungent and heady cocktail, to which animals and humans are sensitive. Its etymology— from the Greek petra “rock”, or petros “stone”, and ichor, “the fluid that flows from the veins of the gods”—refers to an alchemical merging of the celestial and the terrestrial, a phenomenon that appeals to the senses, evoking emotion and memory. More than a scent, petrichor is a reciprocal relationship among hearts. Initiated by water and drawn from air and soil, petrichor is a dream of earth’s release from arid conditions.

Like petrichor, this exhibition plays on form and being. Using ordinary objects—a ball of thread, found wood, plumbing materials—Sankey and Macleod render boundless processes of fluidity and change on a more imaginable scale. In their collaboration, seemingly dissimilar approaches and forms are combined to transform the gallery space into a realm of possibility. The unthinkable—the complexity of Gaia, Earth as purposeful organism, anthropocenic futures—becomes more thinkable. So, like water, their work dreams.

Phillina Sun

This text was commissioned by South Tipperary Arts Centre for the exhibition PETRICHOR / smelling the rain by Anna Macleod and Katherine Sankey, curated by Helena Tobin, running from 7th September – 18th October 2024.

Artist talk and closing performance 12.30pm Saturday 19th October 2024

Dr. Phillina Sun is a writer based in the Northwest of Ireland. IG: phillina.sun.

Anna Macleod is a visual artist and independent researcher based in Leitrim, Ireland. Her work mediates complex ideas associated with contemporary, historical and cultural readings of place through a variety of methods, strategies and processes. She employs quasi-scientific methods, interdisciplinary collaboration, performance and socially engaged activism to critique contemporary landscapes and to build metaphoric spaces for re-imagining the future.

Katherine Sankey is an Australian Irish artist born in Paris and is based in Dublin. She employs sculpture, video, drawing and painting in her installations. Her sculpture uses living plant tissue and human supply lines to engage in the geo-feminist conversation about what we gouge and suck out of the planet. It examines mutation and the human extractive machine of supply and power in a multi species context. Whilst investigating adaptation, colonization and power, Sankey’s art works also explore structure, supply, and degradation; asking questions about nature, the natural, the body, and function.

Host detail, 2023, RHA Gallery, Dublin, tree root systems x 3, chair, plumbing, electrical components, blackout theatre paint, 458cm x 236.5cm x 109cm. Re-situating the viewer and gallery space in the entangled underground where the ‘host’ has upturned the chair, questions the position of humans in relation to our planetary host.

EarthLab: living matters, RHA Gallery Dublin, 2023

Confronting the Human Anthill

exhibition essay by Catherine Marshall

Katherine Sankey’s sculptures do not behave like sculptures. Composed of plant and animal material, industrial detritus and technical devices from the human world, they snake around corners and under doorways, burst from walls, imply mass underground interactions and nose their way through architectural space like wild things in the jungle. Their hybrid identities disturb notions of familiar spaces, all asking the question; how did humankind ever get to believe that they were superior to other forms of life? The issue of human separateness and assumed superiority and the way we occupy space in what often looks like wanton ignorance of other organisms are the familiars throughout Sankey’s work. Her position as an artist parallels that of the writer and poet, Robert Glück. Glück questions our consuming need for certainty in literature. “We are educated to think that we should be able to know the meaning of a piece of writing’ he says and asks instead, ‘but what if the intention of the writing is to throw us into confusion, induce a state of wonder and unravel the basic tenets of our experience?’ (Glück, cited in Elvia Wilk, Death by Landscape, 2022, p. 230) Sankey’s work questions our relationships with every aspect of the world around us. And it adds to our uncertainty by insisting that even when we think we understand those relationships they mutate into something else. We can never get absolute certainty.

Although born in Paris and living in Ireland since 1997, Sankey spent much of her formative years in Australia, still in the 1980s a country on a see-saw between accelerating natural forces and climate change on the one hand and a burgeoning industrial and urban expansion on the other and burdened with the inescapable heritage of Western imperialist cultures. Georgia O’Keefe and Sidney Nolan went out into the deserts of New Mexico and Australia in search of new origin myths, but for contemporary artists like Sankey, the Australian outback was already seriously contaminated by Western ideologies. Although influenced by James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis, it was the mundane sight of the remnants of an old shower with its pipes still sticking out of a wall in a Polish demolition site that gave her the direction she has followed since coming to Ireland.

The formlessness of that site with the entrails of the life it once supported and an inevitable sense of melancholy – also a feature of O’Keefe’s and Nolan’s work - sent Sankey back to linear expression - not the cosy linearity of pencil on paper, not even the work with textiles and thread of her art college days - but the spiky, rusting, fractured lines of old plumbing pipes and electric cables. Those lines are usually concealed, just as the mechanical and plumbing systems of the human body are. They appear in Sankey’s work in installations that project from walls, or hang from the ceilings (you can walk under such objects as the roots of a real tree) or flop over the floor, made up of anything from pristinely polished, copper plumbing pipes, nuts, bolts, and coloured cabling to tree branches, whittled arboreal bones that look incredibly human, all impeccably bolted or jointed together, yet eschewing the romance of the craftwork tradition. Instead they call attention to boundaries and the lack of them, where and how does each life form begin and end, how did it all become so mixed up? When I drift off to my crematory oven how much metal and plastic will be mixed with my ashes? Dark thoughts indeed, but treated by the artist with a whimsy reminiscent of the strange machines in Paul Klee’s drawings. ‘Absurdism’, she says, ‘ is a big part of the practice - grappling through dark humour with aspects of the human condition’.

When a tree with its magnificent trailing roots fell near her studio it offered new vistas through the resultant gap but brought with it the hidden, complex world of its huge root system, entanglements and parasites and the hole that had accommodated them. It led Sankey to install a tree root, still smelling of earth and mould, still imbued with bits of wire and rusting metal, coloured by organic and mineral action in an art gallery, bringing with it a visceral sense of interpenetrating and connecting forces, of constant, invisible activity, of death and decay, but also of life, nature and art, re-positioning the viewer in its entangled underworld. The hole immediately became something more than just a hole. It becomes the void – an echo of the abyss so feared by 18th century writers of the Sublime, prophetic now at a time of climate anxiety.

It makes sense then that when showing at the RHA Sankey’s work spreads itself around. We find it in one of her multi-media installations, Host, near the main entrance, then it disappears but re-emerges, outside the Ashford Gallery as Swallow before invading the architecture of that space. Her love of architecture and the interpenetration of inside and outside as much as her concern for vulnerable organisms and the global scale of human impact on them may have prompted Coral-ations. Here Sankey departed from the tree roots and plumbing pipes invading the building and looked instead at the structures of brain coral, using ceramic modules of sections of coral and combining these with wall drawings that sweep from floor to ceiling in the gallery. In doing so, Sankey reveals the parallels between coral formations and human construction. She imagines segments of the coral, unpicked from their natural forms and extended out to reveal something of their length, so that the viewer can walk inside them, perhaps gaining some sense of that diminishing organism and pondering the vulnerability of the human brain which it so resembles. She is not alone in comparing the human body to nature. Leonardo da Vinci thought similarly and was equally down to earth in his expression of it. ‘The tree of the lungs has its roots in the dung of the liver’, he remarked in his notebooks over five hundred years ago. Sankey’s coral structures share the space with two videos that bring us back to discussion about the hole, but now it is the way we humans make holes in the ground that is the subject of the work. In Handmine a woman humbly lifts soil from the ground with her bare hands, feeling, touching the earth before re-filling the hole and gently restoring the ground. In Craters, the earth is savaged by industrial diggers, exploited by patriarchy for immediate profit. The opposing processes of restoration and destruction, healing and scarring matter to those who live nearby. Biologists increasingly believe that other creatures are far more intelligent than was previously understood, that even plants have the ability to communicate with organisms in their environment, and that research now questions primate exceptionalism.

Sankey’s ideas are big, They find expression through a range of artistic disciplines from drawing, to sculpture in processes that have more to do with industrial technology and assemblage than conventional carving, moulding and casting, but in each individual process her attention to detail and fine finish is of the highest standards. Nuts and bolts are polished before being bolted on to pieces of whittled wood or decaying roots to highlight the absurdity of our lives on the planet. Despite the enormity of the issues she raises, humour remains important. The abstract qualities of complexity and balance in each piece, free us to engage with the absurdity of human action in an un-emotional, clear-headed way. Shakespearian critics have pointed out that it requires more intelligence to enjoy his comedies than his tragedies for which the emotions were a priority. Katherine Sankey’s artwork like Shakespeare’s comedies are about foolish societal behaviour, not tragic individuals. Her purpose is to (as Gluck suggests) induce a state of wonder and help us to unravel the basic tenets of our experience.

Catherine Marshall

Loxodrome (Coral-ations series) 2023, RHA Gallery, 45 x 36.5 x 32cms, ceramic, glaze, basalt. Study on the relation of coral structures to human architecture.

photo courtesy of the artist

Visual Artists' News Sheet | September – October 2023

‘Critique’ essay by Susan Campbell

MY VISIT TO Katherine Sankey’s current exhibition at The LAB Gallery was filtered through the experience of having just had surgery on a broken wrist, shaping the encounter in ways that pivoted around a heightened awareness of the importance of care. When a person, or planet, is vulnerable, care is an often-unspoken need. A form of connection, it shows willingness to pay attention in the interest of doing right by someone or something.

The presented works, all created this year, pay attention to the impacts – infinitesimal to infinite – of mid-twentieth-century atomic-bomb testing and deployment. Drawing on the writings of feminist theorist and physicist, Karen Barad, and the phenomenon of quantum entanglement, the overarching title is, says the artist, “a provocative reminder of just how deeply humans have ‘invaded’, penetrated all living systems”.1 In an accompanying text, Nathan O’Donnell ref-

erences the ‘bomb pulse’ associated with the 1955-63 period: “the spike in atmospheric Carbon-14 produced by the […] more than five hundred nuclear bombs [that] were exploded, above ground, in the open air, around the world, creating an atomic pulse that effectively left a time signature in every living thing on earth.”2

A recent film about J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory that produced this technology, suggests he grew concerned that it could wipe out civilisation. There were myriad precedents to forewarn of unintended consequence, including Hollywood’s popularisation of the novel Frankenstein, not long before the instigation of his Rubicon-crossing project. And so, it continues. Social media is regarded by many to be an unrestrained experiment, and an AI developer recently expressed regret about the dangers of the technology he pioneered.

Sankey’s exhibits materialise humanity’s capacity for care, while addressing its failures to act responsibly. She attentively conjoins manufactured and natural materials to emulate hybrid, mutant states. More uncanny than monstrous, these probe the human-nature problematic by channelling intrigue rather than fear.

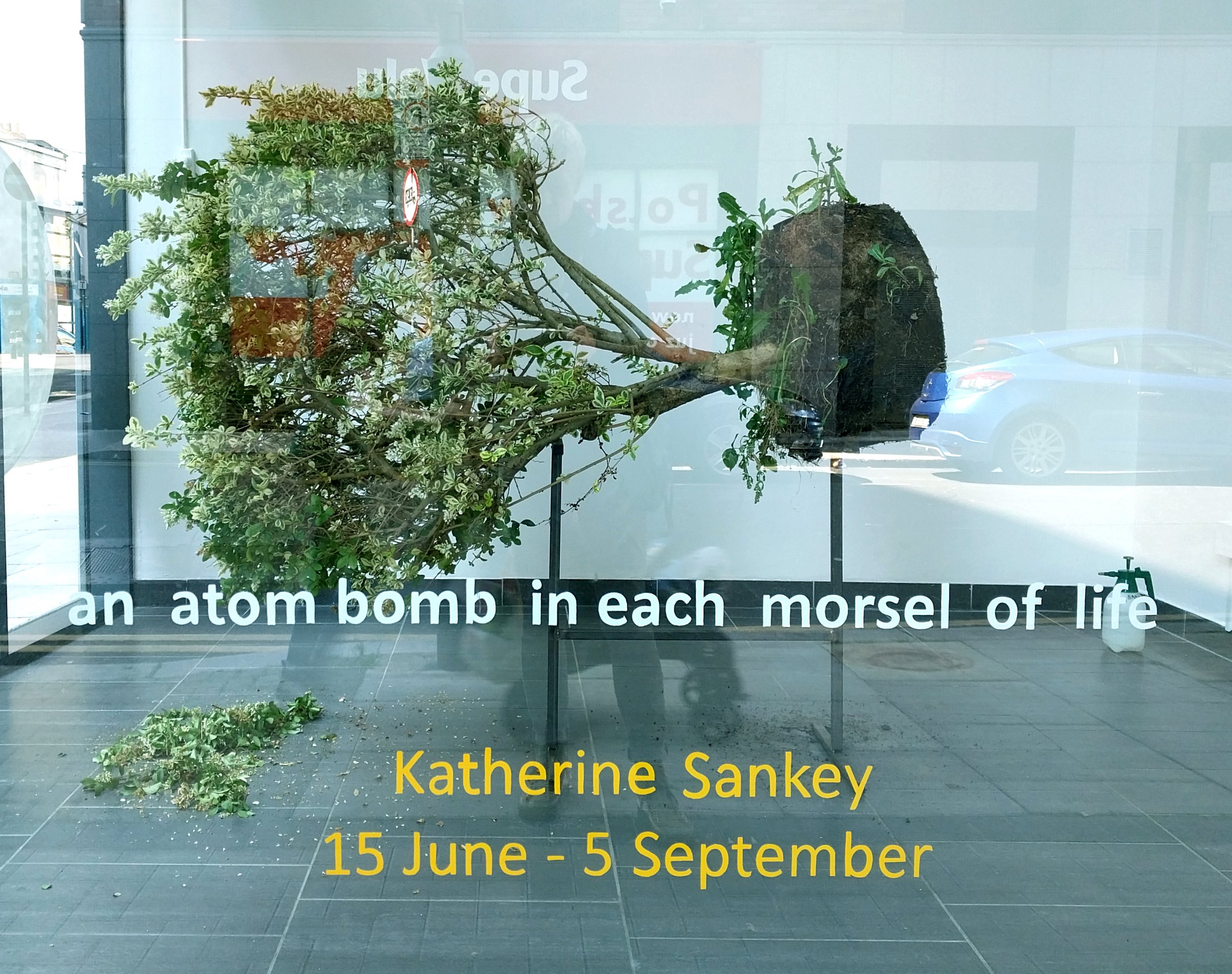

While many are modular, Small Earth (Eden) (2023) features an intact variegated privet, resting horizontally on a steel grid. This upending of a small ‘tree’, a form with multiple symbolic meanings, overturns the principle of the vertical and, with it, the hierarchical structures that shape all kinds of human activity. Concurrently, as the levelling forces of storms, floods, and political unrest become increasingly prevalent, the material condition of this everyday shrub – titled after a paradise perfectly calibrated to sustain life – is emblematic of the exhibition’s concerns. Unplugged from its life source, its creeping desiccation concentrates visitor attention on dying processes (although the artist will try to keep the shrub alive for the duration of the show).

In the main gallery, eight spindly tripod sculptures, titled EarthLab (2023), are built from branches, and sections and junctures of commonplace supply lines. That they bifurcate downwards, from an asymmetric ‘elbow’, imbues them with a lurching attitude, their ‘legs’ resting on the ground or on staggered plinths. Some draw sustenance from stagnant water, while others appear to penetrate the floor or walls – suggesting, for Sankey, connection to the energies of the underworld.3

As surfaces shunt between bark, copper, and white emulsion, I find myself imagining my recently acquired metal-and-bone wrist joint. Similar anthropomorphic qualities in Breather (2023) – a large vine laid out on the floor, trailing plastic tubes analogous to an oxygen supply – recall the feeling of lying prone on a pavement, of being sedated, and later anaesthetised. Gratitude for plugging into a system of care and availing of medical technology is tinged with concern for variables there was no time to research, such as the ecological cost of harvesting titanium.

Upstairs, Activated Entrance (2023) may be a gentle call to action. A sweeping brush leaning against a demarcated section of wall urges us, perhaps, to clear away the debris falling from the tangle of branches in Perc(h) (2023) and take a look at ourselves in the mirror below. Also reflected are crustacean claws that recall the grasping side of human nature.

In Swallow (2023), a proliferation of bleached wood and plumbing overspills a bathroom sink to evoke uncontrolled growth and imbalance, while, nearby, the video pairing Craters and Handmine (2023) links large and small impacts; the massive holes caused by excavation, quarrying and bombing, and a pair of hands disturbing a patch of soil.

With the future of the planet inextricably bound to ours, what Sankey’s works appear to advocate is – above other priorities – underpinning action with appropriate attention to interconnection and consequence. The atomic bomb was justified as ‘the bomb to end all bombs’, but insufficient thought was given to the irrevocable changes it would herald, many of which are still not fully understood. Tethered to humanity’s technological aptitude is the responsibility to go beyond due diligence, acknowledging what it’s not yet possible to know – and caring about that.

Susan Campbell is a visual arts writer, art historian and artist. susancampbellartwork.com

1 Quote from @katherinesankeystudio, 30 May 2023.

2 Nathan O’Donnell, ‘’55-‘63’, exhibition text, published by The LAB Gallery. See below.

3 Ibid.

Swallow detail, 2023, wood, plumbing, hand basin, 75cm x 81.5cm x 58cm Collection OPW Dublin Castle photo: Louis Haugh

an atom bomb in each morsel of life

The Lab Gallery, Dublin, Ireland

14 June - 5th September 2023

Exhibition essay by Nathan O’Donnell

’55–’63

In her 2017 book, The Second Body, Daisy Hildyard sets out to articulate ‘a way of speaking which implicates your body in everything on earth’.[1]

The book begins by problematising the distinctions we make between our bodies and the worlds around us: the animal world, the machine world, the world of microplastic and waste we have generated. Hildyard is critical of any idea of the self as a contained entity, of the body as a defined boundary. On the contrary, her aim is to find a language to express the interconnectedness – the entanglement – of the human and the non-human.

*

In normal life, a human body is rarely understood to exist outside its own skin – it is supposed to be inviolable. The language of the human animal is that of a whole and single individual. … Climate change creates a new language, in which you have to be all over the place; you are always all over the place. It makes every animal body implicated in the whole world.[2]

*

Hildyard refuses to think of the body as a stable container with rigid demarcations. Instead, she proposes that we consider the possibility that we are possessed of a ‘second body’, an expanded, borderless entity, extending across the globe and into the earth, into water, into the air, through infrastructural and political and ecological systems. This second body allows us to conceive of the multiple – infinite – extensions and interpenetrations of the individual with the world.

*

Katherine Sankey’s work is full of entanglement. Her sinuously-assembled, sometimes-monstrous sculptural objects are interlocked, plumbed, entwined, looped together. They have a complex internal circuitry that also extends outward, connecting, at certain key points, to the gallery infrastructures around them.

At these circuit points, they seem uncontainable, as if they refuse to be considered separate, inviolate, distinct from the world around them.

*

The ‘bomb pulse’ is the name given to the spike in atmospheric Carbon-14 produced by the hundreds of nuclear bomb tests that were undertaken in the post-war period. Beginning in 1945 but intensifying a decade later – and continuing until 1963, when they were banned by international treaty – more than five hundred nuclear bombs were exploded, above ground, in the open air, around the world, creating an atomic pulse that effectively left a time signature in every living thing on earth. Even animals at the bottom of the ocean – deep-sea creatures dwelling in the Mariana Trench – show traces of Carbon-14 in their muscles. This was a historically-specific event, taking place across a brief few year(s) of concentrated intensity, but it is also continuing to play out in slow motion. The full extent of its effects remains to be seen. What is clear is that this radioactive fallout has left an atomic date stamp on every part of life on this planet, as indelible as the carbon rings of a tree trunk.

Particle physicist and philosopher Karen Barad argues that ‘matter fell from grace during the twentieth century’.[3] We can no longer separate the material from the immaterial. We no longer have access to the idea of some fixed human scale through which to view the world: large and small interpenetrate, become impossible to differentiate. Temporalities are mutable. The earth is now a sort of test-site, an experimental environment over which we have lost control (if we ever had it), an unstable atmosphere in which outcomes cannot be predicted.

*

In Earth, we see a pair of hands, digging in a patch of earth. It is a repetitive quotidian gesture, familiar to anyone who gardens; the grounding interaction of skin and earth, the simple inquisitive act of uprooting a bit of soil in a backyard. This footage is juxtaposed, on a second screen, by a cascade of images of other, more colossal excavations. Bomb craters. Open cast mines. Building sites. The hole in the earth left after a tree has been uprooted.

Sankey talks to me about taking a walk in a park near her home, where the Council were removing dislodged trees. She talks about getting up close to the disrupted tangle of roots and earth and microcosmic life, insects, soil, a whole complex ecosystem, and being struck by a sense of terror, brought face to face with a world-within-our-world that is strange and monstrous to us, an entanglement of species and matter, a knot of ecological wiring which is inscrutable to us and without which we could not survive.

*

The Manhattan Project not only unlocked the power of the atom, creating new industries and military machines, it also inaugurated a subtle but total transformation of the biosphere … we need to examine the effects of the bomb not only at the level of the nation-state but also at the level of the local ecosystem, the organism, and ultimately, the cell. … America’s nuclear project has witnessed the transformation of human ‘nature’ at the level of both biology and culture … turning the earth into a vast laboratory of nuclear effects that maintain an unpredictable claim on a deep future.[4]

*

Sankey’s work modulates between different scales, sometimes expansively large, sometimes granular and forensic. The question of scale is a key preoccupation for the artist. It is one of the key collective challenges we face, as we struggle to imaginatively conceive of the Anthropocene, climate destruction, and the entanglement of matter and body. These are concepts that combine an almost astral metaphysical quality with raw political and social urgency.[5] They require thinking across several scales simultaneously and immediately – the human, the global, the cosmic, the subatomic.

This is more than an imaginative exercise. As Barad notes, ‘[w]hen the splitting of an atom, or more precisely, its tiny nucleus (a mere 10−15 meters in size, or one hundred thousand times smaller than the atom), destroys cities and remakes the geopolitical field on a global scale, how can anything like an ontological commitment to a line in the sand between “micro” and “macro” continue to hold sway on our political imaginaries?’[6]

This folding of micro and macro is a feature of Sankey’s practice. Her sculptural work is rarely scaled to the (average, Modular, Vetruvian) human body. Occasionally the body might figure as a tangential affordance – she sometimes incorporates pieces of furniture, for instance, a table, a kitchen chair, with their suggestions of a human occupant or user. Or the body might feature as a reference or index; Breather, for instance, suggests to me the body of a supine giant. But otherwise, it seems to me, her lens is not focused on the human; instead it ranges back and forth between the molecular and the monstrous.

On my last visit to the artist’s studio, Breather is laid out on the ground, covered over in a sheet of tarpaulin. It has returned from another show and is ready to be transported on to the Lab. It looks like a huge dead body wrapped in an enormous body bag.

*

It is not only at the level of the particle that entanglement has come to be recognised. Even in the past decade, there have been significant developments in our understanding of the entanglements of natural ecosystems: forest root systems, mycelial networks. As has been recently observed, James Lovelock’s and Lynn Margulis’s famous ‘Gaia hypothesis’ – the case for viewing the earth as a living, self-regulating organism, much-derided within the scientific community when it was first published in the 1970s – has in some ways been vindicated. Meehan Crist has noted that, in the intervening decades, research has concluded that ‘however improbable, teleological, or untestable it [the Gaia hypothesis] may be, it contains a nugget of truth more axiomatic than anyone would have guessed’.[7] We recognise today the earth’s complex regulatory patterns, a delicate stability built on the manifold interrelationships and feedback-loops between organic materials and environmental conditions, the balancing flows of sea levels and weather systems and so on. There are logics at play that transcend the objections to the Gaia theory, predicated as it is on a belief in the planet’s ‘sentience’. Ultimately – and perhaps this could be considered a key blind-spot in our conception of sentience itself – we have fallen victim to our own crude fiction of inviolability, our impulse to see ourselves as distinct from the world around us.

*

Sankey’s structures have a mutant quality. They are possessed of an uncanny strangeness, otherworldliness, materials evolving and mutating in apparent symbiosis – bleached wood bark merging with copper fixtures, porcelain, electric wiring. At a molecular level, genetic mutation can be understood as an evolutionary process, a mechanism for surviving hostile environments, a sort of DNA stress response. Sankey’s objects are mutant in this regard – like seismic mutations, forming in response to our own monstrous acceleration, survival mechanisms activated in response to the shifting – deteriorating – ecosystems that sustain us.

There is also something of cyborg about them, composed as they are of organic and mineral elements, fusing and extending into the infrastructure around them. One of the largest works in the exhibition, EarthLab,is composed from a set of 8 branches and stands vertical, about four metres high, its ends plumbed into the walls and floors and painted over the way such joins and fixes are often painted over, clumsily, not quite concealing the disruption.

From a certain angle, they have a sci-fi aspect too, reminiscent of the Martian invaders in War of the Worlds. They feel elemental, even; Sankey describes them as ‘chthonic’, aligning them with the Greek gods of the underworld. Drawing dark energies from under the earth, these are creatures animated by the unseen – the root systems, the electrical wiring, the water being funnelled and maintained and channelled underground. They are tapped into the infrastructure, fuelled by the natural resources we pump around and through our habitats; monstrous mutations assembled through the sheer kinetic force of the atomic energies – the bomb pulse – we have unleashed upon the world.

*

The entire world is entangled with the explosion [Hiroshima], a global dispersal of the bombing. The bomb continues to go off everywhere (but not everywhere equally). The whole world is downwind. … Histories, geopolitics, nothingness, written inside each cell.[8]

*

There is a danger here – a danger of which Sankey is keenly aware – of reducing ecological material to the status of metaphor. This is a point Barad makes too: to reckon with the Anthropocene, and with climate catastrophe, conventional understandings of matter and meaning need to be undone. Sankey recognises this, and reflects upon it within the work, taking what she recognises as settler-colonial practices – the bleaching of barkbranches, the reduction of organic material to sanitised tool – and utilising them as critical commentary. In a way, her work might be read as a satire of over-identification, a heralding of the monstrous future we are building.

I also see Sankey’s work in relation to contemporary practices in Ireland which reckon with questions surrounding land and environment and legacy: ecological, feminist, critical work by artists like Deirdre O’Mahoney, Michele Horrigan, Seoidín O’Sullivan, or those artists – again mostly women artists – whose work deals with farming and its ramifications, Maria McKinney, Lauren Gault, Katie Watchorn; work that attends to environmental mismanagement, questions of stewardship and cultivation as well as wreckage. These are artists whose work takes vastly different forms, of course, but with some key concerns in common: how to conceive of our relationship with the environments around us, across time, across scale.

*

In the Cube space by the entrance sits Small Planet, a work with a quite different quality. In this space, a small tree is held horizontally in mid-air, supported on a steel frame. Unlike the other tree-based structures in the exhibition, this one is living. The roots are not grounded exactly but the earth is intact around them. There are weeds growing out of the soil, which is plumbed with a pipe extending into a glass bowl full of water. This is a strange Quixotic arrangement, an experiment in sustaining life in suspended conditions. It is like an assemblage from a different sci-fi sub-genre: an image of cultivation in a disassembled future. The title refers to the home planet of the Little Prince – a small asteroid known as B 612 – with its volcanic activities and its ungovernable baobab trees. Small Planet suggests, maybe not quite hope, but a will to persist, an idea of continuance. Throughout the run of the exhibition, the artist will do her best to keep the tree alive, trimming the leaves and letting them drop, accumulating like hair on a salon floor.

[1] Daisy Hildyard, The Second Body (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2017), 12.

[2] Ibid., 13.

[3] Karen Barad, ‘No Small Matter: Mushroom Clouds, Ecologies of Nothingness, and Strange Topologies of Spacetimemattering’, in Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Elaine Gan, and Nils Bubandt (eds.), Art of Living on a Damaged Planet (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 103.

[4] Joseph Masco, ‘Mutant Ecologies: Radioactive Life in Post–Cold War New Mexico’, Cultural Anthropology, 19:4 (2004), quoted in Barad, ‘No Small Matter’, 109.

[5] Jodi Dean identifies this paralysing incapacity to conceive of climate change as a ‘whole’, arguing instead for the adoption of a partisan or ‘anamorphic’ perspective, a perspective that acknowledges the viewer’s necessarily limited position. See Jodi Dean, ‘The Anamorphic Politics of Climate Change’, e-flux journal, 69 (2016): 5.

[6] Karen Barad, ‘No Small Matter’, 108.

[7] Meehan Crist, ‘Our Cyborg Progeny’, London Review of Books, 43:1 (7 January 2021): 11.

{1] Karen Barad, ‘No Small Matter’, 106.

Small earth (Eden), 2023, variegated privet, earth, plumbing, water, box steel, Katherine Sankey, ‘an atom bomb in each morsel of life’, The LAB Gallery, 15 June – 5 September 2023. Photo courtesy of the artist

EarthLab detail, 2023, The Lab Gallery, Dublin, 8 free-standing sculptures: tree branches, plumbing, electrical components, water, roots, glass. 2m - 4m high, installation dimensions variable. Photo: Louis Haugh